Talking Lingo

A designer's perspective toward language and meaning, from semiotics to Klingon.

Jul 01, 2019 – by Dean

So I’ve always found myself a little obsessed with language — learning, making, playing with it. As a mere 4th grader, I filled the pages of my notebooks with systems of scribbles spanning letters A through Z, my own personal ciphers and meaning-making. I always found it fascinating to create a world and culture of my own through letters and symbols. Today, I’ve found a new way to create languages of my own through type and iconography. One small change to the design of a letter affects the flavor of a paragraph or the meaning of a word; designers can harness that modularity to build our grids and pages. Modularity is central to what I perceive as design, but it can also extend into how we understand language itself.

MEANING IS MODULAR

In school, I loved learning about semiotics (a fancy word for the study of signs and symbols). As it turns out, humans are meaning-making machines, and the meaning of visual symbols evolve naturally over the course of how we use them. Ferdinand De Saussure, the father of semiotics, also widely regarded as the father of linguistics, studied not only visual language, but the formation of verbal language, beginning a century of analysis on the way we speak.

Can our speech be designed the way our visual languages are? As visual communicators, our job is to create meaning out of modular shape systems — but what of verbal language?

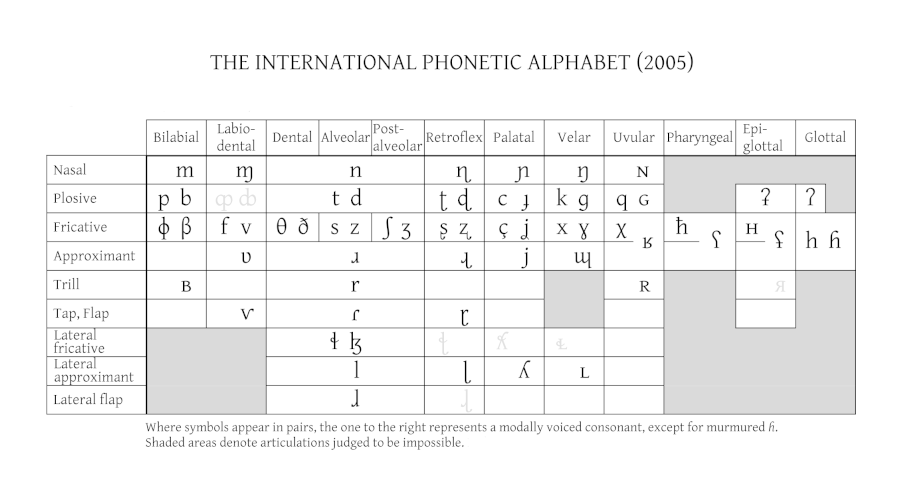

Treating grammar and pronunciation as modular creates an entirely new medium. Which is what linguists have known for the last 100 years. They've categorized sounds in every language — consonants, vowels, and even clicks — into a component-based system. The chart below is one example of a series of sound categories; this one is just the consonants in the phonetic alphabet. As a set, they describe parts of speech, our verbal building blocks.

With this, we can better understand modern linguistic design problems. If semiotics can be a solution for design, why not linguistics?

DESIGN BRIEF: GUTTURAL, HARSH, & ALIEN

Klingon, believe it or not, is an interesting design problem. Before 1984, Star Trek’s Klingonese included only several lines of harsh, guttural gibberish, quickly created by the show's writers to introduce the vast Klingon Empire. To develop a fully speakable language, the writers commissioned Marc Okrand, who used that early gibberish as a spring-board.

To understand how he did that, let's refer back to our Phonetic Alphabet chart: moving from left to right, the right extremes are the hardest sounds for our tongue to make, and the least common in many languages. What better to use as the standard for an alien language? Okrand expanded the Klingon vocabulary by taking the rarest sounds and rules known in Western linguistics.

What's more, the grammar he implemented was increasingly unusual. Klingon has an object-subject-verb word order, a structure used by only 1% of languages today. While in English, we'd say "She loves them," an object-verb-subject order says "They love she." Just one grammatical rule in a suite of oddities that were built into the alien language

DESIGN BRIEF: ELEGANT, FLOWING, & ANCIENT

You may remember the elves of JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings as ancient, wise, and regal, nomadic beings that spent their existence in migration. Tolkien wanted their language to evolve over time, showing the change in dialects and culture. In linguistics, this is considered Diachronic meaning. Seen in English and Old English, phrases and pronunciation have evolved over the course of Western civilization. We've adopted words from other cultures; slang becomes standard; standards are constantly changing.

In Lord of The Rings lore, the old Elvish language Quenya evolved as the Elves migrated, eventually creating Sindarin, the language commonly spoken in the LOTR films and book series. Tolkien devised both languages, creating a fully fleshed out vision of Elvish heritage. Its flowing and graceful cadence was based on many sounds in the old Celtic tongue (in which Tolkien was well-versed). It's striking to hear the familiarity between the two languages:

DESIGN BRIEF: FAMILIAR, FLEXIBLE, FOSTERING UNIFICATION

Languages can be designed with good intentions, not just for good storytelling. L.L. Zamenhof created Esperanto as part of an ambitious (and idealistic) goal of unifying Europe during the late 1800s. Born in 1859 to a Jewish family in Poland, Zamenhof lived in a melting pot of Russian, German, Polish, and Jewish people. Having grown up seeing those cultural tensions, he started publishing his new lexicon under the pseudonym “Doctor Esperanto.”(Forget elvish and Klingon, we’re solving real problems here!)

Known as an A Posteriori language, Esperanto was built using other languages as a foundation, to make it familiar and easy to learn. While it may not have brought us everlasting international peace, people across the world do speak Esperanto to this day. That's what I'd call a well-made language.

This is all, of course, just skimming the surface. There is so much to explore at the intersection of design and linguistics—and I encourage you to do it. Maybe the world will start investing in language design and one day, we’ll be speaking IBM-ese or Facebookian *shudder*.

In closing:

Le hannon! Thanks!

— and —

Qapla'! Goodbye!